The French Sanson Family As Cartographers Of Finland In The 17th Century

Andreas Bureus, Founder Of Swedish Scientific Cartography

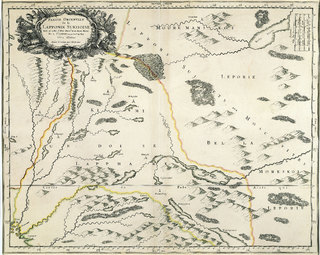

Cartography became scientific in Sweden-Finland at the beginning of the 17th century, when the Swedish cartographer Andreas Bureus (1571-1646) started the mapping of the North based on scientific measurements.LAPPONIA, the map of the northern parts of Scandinavia was the first, published in 1610, and the map of the whole of the Nordic Countries was finished in 1626. At the same time also the Swedish Survey Board began its activity, as well as the corresponding institute in Finland in 1633. The excellent map of Bureus served as an example to later Central European cartographers for nearly two centuries.

Royal Geographers - The Sansons Family

The centre of the production of geographical maps was moved from the Netherlands to France at the beginning of the 17th century, and not least because of the activity of the Sanson family. Very clear versions, based on Bureus,on the areas of the Nordic Countries and Finland were presented from the middle of the 17th century onwards by the cartographers belonging to the French Sanson family, in two generations. The cartographic activity in the family was started by Nicolas Sanson senior (1600-1667). The story goes that the only property that Nicolas had when he moved to Paris was a map of old Gallia or France that he had drawn.It happened ,however,to please Cardinal Richelieu, leader of France,and this is how Nicolas got into the favour of the court and was nominated royal geographer, teacher of geography. The title was passed on in the family. Nicolas Sanson was a most productive cartographer:he published approximately 300 maps in all and atlases on all the four known continents. All three sons of Nicolas Sanson, Nicolas Sanson junior, Guillaume and Adrian, continued their father's work. Nicolas's son-in-law Pierre Duval was also a well-known cartographer.

A Map Does Not Take A Stand On Borders

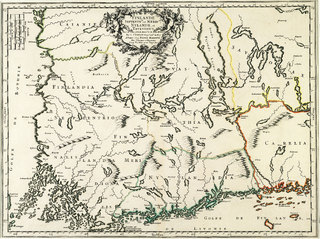

An interesting point about the Sanson interpretations of Sweden is the fact that in their maps the national borders are drawn very clearly. As late as in the 16th and 17th centuries the cartographers and geographers were cosmopolitan in the respect that they hardly stopped at such details as border issues. There were, however, signs of some kind of geopolitical thinking: e.g. in Italy some principalities were presented with their borders as early as in the 16th century, but generally this custom was even avoided. It is a well-known fact that e.g. in Finnish history the eastern border was not defined on the map in the first peace treaties with Novgorod, but the border was defined according to place names.This took place at the treaty of Pähkinäsaari in 1323, when one landmark after another was listed from Rajajoki in the Karelian Isthmus up to present-day Savonlinna-Varkaus area, but from there on the border was mentioned to continue to "salt sea", undoubtedly because the inner parts of Finland were practically uninhabited. The following eastern border was defined just as loosely at the treaty of Täyssinä in 1595. The border followed at its southern end the old Pähkinäsaari treaty border, but turned north around Savonlinna-Varkaus via Iivaara in Kuusamo to the Artctic Sea. Even the Stolbova treaty border (1617)- when the county of Käkisalmi and Karelia became part of Sweden - was not marked on the map.The northern border of Sweden was also complicated by the fact that Lappland was until the 18th century a common taxation area to three countries, Sweden-Finland, Denmark-Norway and Russia.

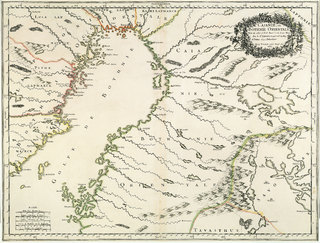

The Aims Of Great Power Period Sweden Concerning The East

It is well-known that King Charles IX was interested in Lappland, and this is why he gave Bureus as his first task to map Lappland. Charles's successor, King Gustaf II Adolf was equally interested in the north and east, and his wishes came partly true at the Stolbova treaty in 1617. The aim of Sweden had been from the 16th century to bar Novgorod-Russia from western seas and thus get hold of the profitable east-west intermediate trade. This becomes clear in Gustaf Adolf's speech to the estates after the Stolbova treaty. The King stated that the new border increased remarkably the security of Finland, Lake Ladoga being the border lake of the nation. On the southern side of the Gulf of Finland the Estonian border against Russia - Estonia was part of Sweden in the 17th century - was the line of Lake Peipus and the River Narva. There was a tendency towards so-called natural borders against Russia.

After King Gustaf Adolf had died in battle in Lützen in the Thirty Years' War in 1632 the idea of natural borders against the east was further developed by the General Governor of Finland Count Pietari Brahe. Brahe proposed that the sphere of influence of Sweden should reach the White Sea. The goal was the so-called three-isthmus border, where the border would run via Lake Ladoga and Ääninen to the White Sea. This area was mainly inhabited by Karelian-speaking population, so Brahe's plan had a certain logic as far as national and linguistic aspects are concerned. It is a totally different matter if they were considered important in the 17th century; Brahe's motives may have been mostly political and economical.

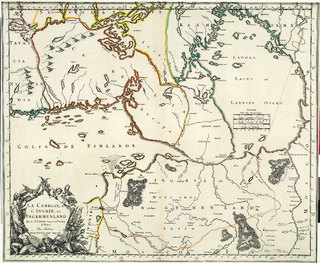

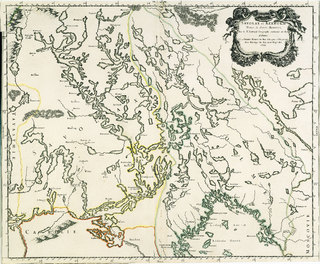

The Eastern Border According To The Sansons

Barely before the map of the Nordic Countries was published by Sanson a Dutchman Joan Blaeu published a map on the Finnish Grand Duchy (1662), where in fact the eastern border of Finland is described quite truthfully. Nicolas Sanson treats the eastern border less in details in the maps published in 1666-1669. It even looks like the relations between Sweden and France,which developed into a warm alliance during the Thirty Years' War, despite the fact that France represented catholicism and Sweden purely protestantism and Lutherism, would reflect directly in the atlas of Sanson. The French court may have heard rumours of the dreams of both the King and the General Governor of Finland. So Sanson drew the eastern border to run via the River Neva and Lake Ladoga to the River Shuja, which flows into Lake Ääninen around present-day Petroskoi, from there across Ääninen to Shalja(Puutoinen), and from there towards north-east following the coast of the White Sea, leaving, however, the coastal area to Russia.The same eastern border can be met in the map version of Nicolas Sanson junior,with the difference of the northern border of Sweden-Finland ending via Lake Inari and the River Näätämö in the Arctic Sea. It is quite a coincidence that the Finnish and German troops were approximately on this line on the east front in the World War Two!

The Sansons seem to have been somewhat uncertain about the ownership of the areas on the other side of Lake Ladoga, because Sanson senior does not see any need to connect these areas with Finland in his provincial maps.Käkisalmi is regarded as the easternmost province. In his provincial maps Sanson senior has made a compromise so that the White Sea has actually been drawn in a wrong place, too far in the west, almost on the level of Repola.

In the map of the county of Käkisalmi recognizable landmarks are, when we follow the border to the north-east Tulemajärvi, Torasjoki, Porajärvi, Himoila, Koirajärvi, Vonkeri, Soverka and Lendila or Lentiira, scattered here and there. From here north the border is rather vague, until new landmarks are found in Lappland. The old border place Iivaara in Kuusamo remains far inside the Finnish border, when Sanson drew the border east of Kuittijärvi and Pääjärvi. From here the border goes on to Inari and the Artctic Sea. Following the example of Bureus several Lapp villages were marked in Lappland,e.g. Sompio, Kemi,Kolajärvi, Sodankylä, Kittijärvi and Maanselkä. The area of Lappland was divided according to the rights of exploitation into the Lappland of Kemi, Tornio, Luulaja, Piitime and Uumaja. The Lappland of Kemi was the only one really on the Finnish side, because even the Lappland of Tornio was considered a Swedish province and diocese according to secular and clerical division.

School Of Cartography

The French school of cartography born around the Sanson family and family members is characterized with clarity and purity of style so typical of the Baroque period. Unlike in Central Europe and Russia there are hardly any forests drawn in Finland; and in fact the whole of Finland was nothing but forest! Almost the only exceptions are the forests of Rautalampi and a few stretches of forest scattered in Lappland. Imaginary mountain ranges have been drawn to divide Finnish provinces e.g. between Uusimaa and Varsinais-Suomi, mountains can also be seen according to the Sansons at the provincial borders of Uusimaa, Tavastland and Karelia. In reality they stand for watersheds, such as Salpausselkä, so the Sansons and their example Bureus are not so wrong after all.

The Sansons have naturally had a lot of difficulties with the orthography of the Finnish names, because even Bureus found them quite painful. Besides the orthography of Finnish names was not fully developed in the 17th century. The names are, however, easily recognizable. In spite of their deficiencies and mistakes the Sanson maps give a surprisingly right picture of Finland, and its hundreds of place names also give the right figure to the local population. The maps offer a fascinating view over the Finland that is getting shape.

Text: Heikki Rantatupa